Validate your AI or Platform Idea in 40 Engineering hours. Talk to our Expert →

OCR is often treated as the starting point of document intelligence. Once text is extracted, the assumption is that understanding can follow. In practice, many document systems fail not because models are weak, but because the kind of text they operate on is fundamentally mischaracterised.

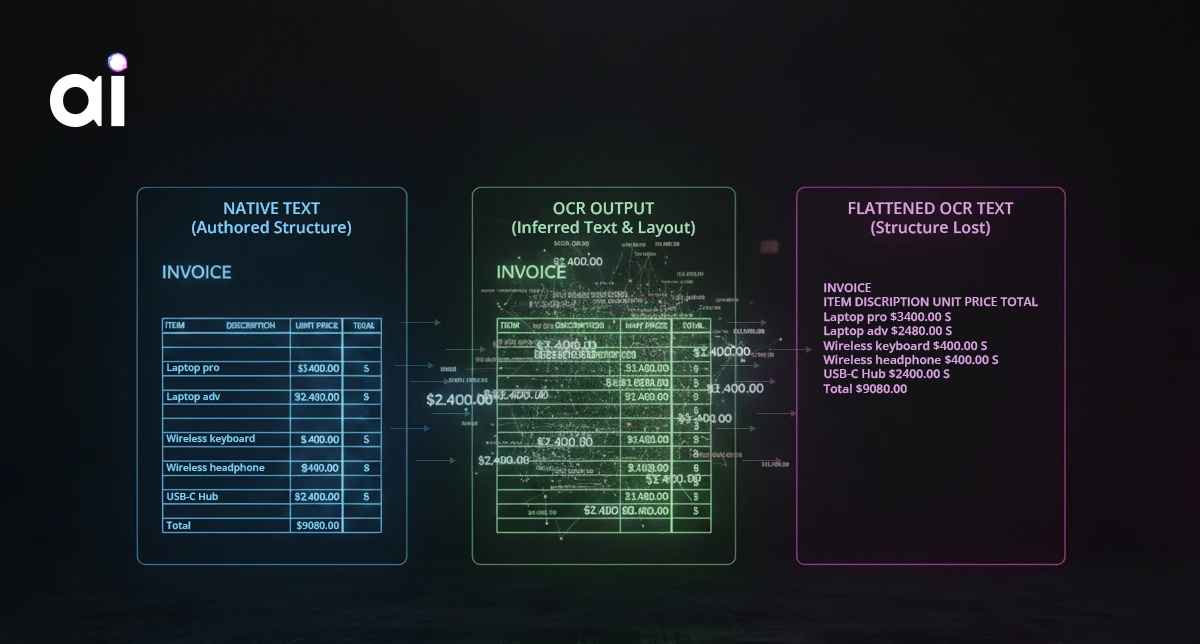

Text does not enter a system in a single form. How text is obtained determines what information survives and what is permanently lost. Improving OCR accuracy alone does not address this problem, because character correctness and document understanding are not the same thing.

Native text comes from documents created digitally. In these documents, text is not inferred; it is authored. Reading order, tables, headings, and hierarchy exist because someone explicitly defined them.

When native text is available, the system is not reconstructing meaning. It is accessing a representation that already preserves intent and structure. This does not guarantee correctness, but it sets a high ceiling for what downstream reasoning can achieve.

The most damaging mistake in document pipelines is treating native documents as if they were scans. Converting them into images and re-running OCR discards certainty and replaces it with approximation. Once structure is destroyed, no downstream model can restore it reliably.

OCR operates under very different constraints. It starts with pixels rather than symbols and infers characters from visual patterns. What it produces is a best-effort reconstruction of text, not a faithful representation of authorial intent.

In practical terms, OCR provides three things:

What it does not provide is knowledge of why those characters exist, how they relate across the page, or which relationships are meaningful. OCR works locally. It evaluates small visual regions and decides which characters are most likely present. Structure that is not visually explicit must be guessed, and guessed structure is fragile.

A PDF may contain native text or only images. OCR is essential for the latter and harmful for the former. Treating both as equivalent inputs silently degrades information before any intelligence is applied.

OCR is often evaluated by how accurately it converts pixels into characters. If the extracted text looks correct, the assumption is that the system now “has the document.” This assumption breaks when documents are used for reasoning rather than reading.

Consider a table that was printed, scanned, and then processed by OCR. To a human, the meaning is obvious. Rows represent records, columns represent attributes, headers define semantics, and alignment encodes relationships.

After scanning, none of this meaning exists explicitly. OCR may correctly recognise every character. Numbers are accurate, headers are spelled correctly, and confidence scores are high. Yet the system does not actually know which values belong to which headers, whether a number is a total or an individual entry, or whether a blank cell represents missing data or intentional separation.

The text is correct. The meaning is not recoverable with certainty. This is not an OCR failure. It is a representation limitation. OCR answers the question of which symbols appear on the page. Understanding requires knowing what those symbols participate in.

Most OCR-driven failures are not random. They emerge in predictable situations where visual cues are insufficient to encode logic. Tables and multi-column layouts rely on spatial alignment rather than explicit relationships. Scanned documents introduce skew, noise, and distortion that humans compensate for instinctively but machines cannot.

These conditions are normal in enterprise documents. They expose the boundary between reading text and reasoning over documents.

Layout-aware parsing exists to reduce irreversible loss. Instead of flattening text into a sequence of characters, it attempts to preserve grouping, hierarchy, and spatial relationships that are necessary for interpretation.

Layout awareness does not create understanding, but it preserves the conditions under which understanding can later emerge. It acknowledges that meaning often resides in structure, not in characters alone.

Many teams attempt to solve document intelligence problems by improving OCR quality. This yields diminishing returns because the bottleneck is rarely character accuracy.

Better OCR reduces transcription errors. It does not restore destroyed structure. It does not recover intent. It does not correct upstream misclassification of document type.

When OCR output is treated as equivalent to native text, downstream systems inherit uncertainty they cannot resolve. What appears to be a modeling problem is often a representation problem introduced much earlier.

No system can reason over information that never survived extraction. Intelligence cannot exceed the quality of the representation it operates on.

OCR is necessary infrastructure. Native text is a privilege when available. Layout-aware parsing is a safeguard against silent loss.

Document intelligence does not begin with models. It begins with how meaning survives the moment text enters the system.